In the same text as contains this post’s title, General Lavr Kornilov wrote “People of Russia! Our great motherland is dying. The hour of her death is near.”1 The country he loved and had fought for much of his life, he believed, was in shambles. A man of law and order, by the time he led his attempted coup, Kornilov believed only a strong authoritarian figure could bring peace and discipline to the state.

Prior to 1917, Kornilov had spent many years in the Russian military. Born to a military father in western Siberia, he attended a military academy and moved quickly up the hierarchy. By World War I, he was a high-ranking general.2 In 1915, he was captured and imprisoned by the Austro-Hungarians, but his subsequent escape and return to his unit earned him national renown and war-hero status.3

Several incidents undermined Kornilov’s faith in the provisional government. After the fall of the imperial government, he was given command of the Petrograd military district. Two months later, however, Foreign Minister Pavel Miliukov sent a telegram to the Allies stating that Russia planned to continue fighting in World War I. The leak of this telegram to the public sparked massive demonstrations in Petrograd.4 Kornilov worked to suppress these uprisings and restore order to the district; he had devoted significant effort to the Great War, so the notion that it was all for naught was unacceptable. However, the provisional government would not allow the use of force, and after Miliukov had resigned, it invited the Petrograd Soviet into a coalition. Kornilov viewed this concession to the masses as weakness and quickly resigned his post.5

The general soon returned to the front lines of World War I. After the unsuccessful July offensive, he pushed for harsh punishment (i.e. the death penalty) of soldiers that refused to fight. However, he also maintained that both officers and soldiers were at fault in the defeat. Prime Minister Kerenskii appreciated this nuanced view, and appointed Kornilov Supreme Commander-in-Chief.6

Kornilov’s acceptance of the position, however, came with a price. Most troubling to Kerenskii was Kornilov’s request that “his responsibility would be to his own conscience and to the whole people.” Read literally, this would give Kornilov the power of a dictator. After some debate and a trade-off, Kornilov agreed that “responsibility… to the whole people” included responsibility to the provisional government.7 Kerenskii, however, remained suspicious of the new commander.8

In August, Kerenskii sent Kornilov to Petrograd to restore order after the fall of Riga triggered uprisings.9 Soon, however, a visit from Vladimir Lvov further complicated relations between Kornilov and Kerenskii.* Lvov told Kornilov that Kerenskii was eager to resign as prime minister, which may or may not have been true. The next day, Kornilov told Lvov that the best way to stop a Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd would be to transfer civil and military power to him.10

Lvov soon informed Kerenskii that Kornilov wished to seize power and become the military dictator of Russia. His suspicions confirmed, Kerenskii immediately dismissed Kornilov. However, he could not find a replacement for Kornilov, and reinstated him within a few hours.11

Kornilov had believed that when Lvov visited him, he was relaying the wishes of Kerenskii. He assumed that Kerenskii was on board with his own assumption of power. His dismissal came as a complete shock. When Kerenskii reinstated him, Kornilov came to believe that Kerenskii was politically hostage to the Petrograd Soviet. He saw the back-and-forth actions and Lvov’s information as a “send help” signal.12

Thus, Kornilov sent troops to march against the Petrograd Soviet, and sent a telegram informing the provisional government of his decision to do so. A panicked Kerenskii informed the Petrograd Soviet and ordered them to defend the city.13 The supposed coup was quickly shut down and Kornilov was arrested.14

The Kornilov affair has been a point of contention among scholars. Historians from the USSR often exaggerate the heroism of the Bolsheviks, and utterly demonize Kornilov, as in this article. In contrast, other historians depict Kerensky as a manipulative scoundrel who tricked Kornilov into invading Petrograd, as this article points out. Both sides have validity, but much of what happened is very muddled and shrouded in mystery – only Kerenskii and Kornilov (and possibly Lvov) know exactly what transpired.

Ultimately, the Kornilov incident was quite a mess of conflicting stories and miscommunication which had several repercussions. It severely discredited Kerenskii in the eyes of the public, and the successful defense by the Petrograd Soviet increased its authority. Additionally, the incident heightened fear of counter-revolutionary activities, sparking a new wave of Bolshevik activity that contributed to the October Revolution.15

*I cannot recommend enough that you read up on Lvov’s involvement in this incident. The more I read, the shadier Lvov seems. He comes across like Varys from Game of Thrones – intent on stirring up trouble, with highly suspect motives.

Notes

- Lavr Kornilov, “Kornilov Responds to Korensky,” Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, Link.

- Sean Kalic and Gates Brown, Russian Revolution of 1917: the Essential Reference Guide (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2017) 79-81, Link.

- Harvey Asher, “The Kornilov Affair: A Reinterpretation,” The Russian Review 29, no. 3, 1970, 286-300, Link.

- Nicholas Freeze, Russia: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 280-7.

- Asher, “The Kornilov Affair: A Reinterpretation.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kalic and Brown, Russian Revolution of 1917, 81.

- Ibid, 80.

- Vladimir Lvov, “Dealing with Kornilov.”

- Kalic and Brown, 81.

- Ibid, 81.

- Asher, 296-300.

- Kalic and Brown, 81.

- Freeze, 288.

I’m with you on Kornilov!!! Your post does justice to the complexity of the situation and the shifting grounds on which the affair unfolded, but it also makes all of the zig-zagging and waffling make sense. Nice! And those articles you cite are wonderful — especially the 50 year retrospective from the Current Digest (everyone reading this should click on that link and just try to orient yourself to how far-reaching this event was for the history of the revolution).

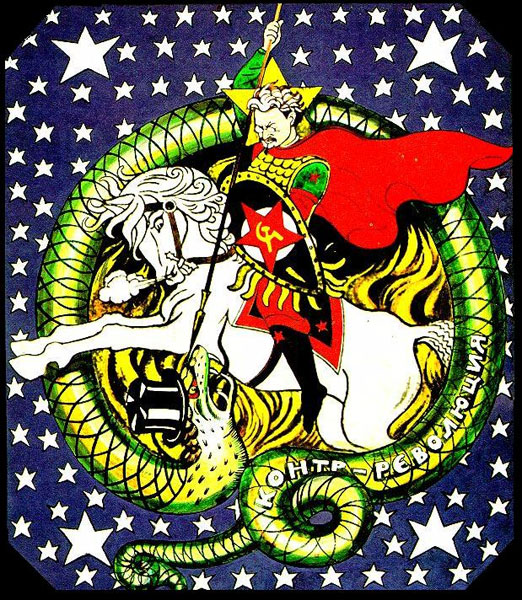

Also, thanks so much for including my very favorite Trotsky poster. Spectacles and all.

But you are wrong about Varys (IMO ;-)). Yes, he’s a schemer, but he has the greater good in mind. And he gets kinder in seasons 6 and 7.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! It took a while to make sense of all the events, especially because some sources left important things out that other sources included. None of them seemed to have the complete story! Personally I still don’t trust Varys haha

LikeLike

The Kornilov Affair can be interpreted in many different ways. You did a great job bringing in the multiple perspectives on this one event. Your extensive research helps clarify some of the muddy details of the whole thing. Great job!

LikeLiked by 1 person